- Carolingian Renaissance

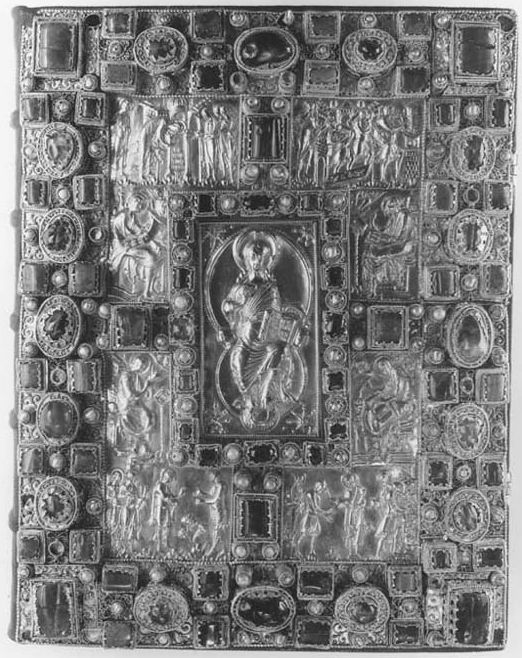

- An intellectual and cultural revival of the eighth and ninth centuries, the Carolingian Renaissance was a movement initiated by the Carolingian kings, especially Charlemagne, who sought not only to improve learning in the kingdom but to improve religious life and practice. Although once understood as an isolated, shining beacon in an otherwise dark age, the Carolingian Renaissance, or renovatio (renewal, or renovation) as it is sometimes called, is now understood to have roots in the Merovingian world and influence on later developments. Despite its foundations in an early period, the real impetus for the movement came from Charlemagne, who sought to reform learning and literacy, improve the education of the clergy, and provide at least a basic understanding of the faith to all his subjects. Toward this end, he attracted a large number of scholars from across Europe to assist him. They laid the foundation for even greater accomplishments in the two generations following Charlemagne's death. Indeed, during the reign of Louis the Pious, as well as in that of Charles the Bald, who consciously modeled his reign on his grandfather's, Carolingian scholars produced beautiful manuscript illuminations, copied and wrote numerous books and poems, and involved themselves in theological controversies. Although the renaissance never accomplished the goals Charlemagne intended and reached only the upper levels of society, it did provide an important foundation for cultural and intellectual growth in the centuries to come.Although the roots of the renaissance can be traced to the reign of Pippin the Short and even back into the seventh century, the movement was inspired by the reforms of Charlemagne. Indeed, the program of reform and renewal that brought about the emergence of the renaissance was one of the fundamental concerns of the great Carolingian ruler. In two pieces of legislation, the capitulary Admonitio Generalis (General Admonition) of 789 and the Letter to Baugulf written between 780 and 800, established the foundation for the Carolingian Renaissance. In the Admonitio Charlemagne announced the educational and religious goals and ideals of his reign, which involved the improvement of Christian society in his realm and, at the very least, providing all people in the kingdom knowledge of the Lord's Prayer and Apostle's Creed. He sought to improve the moral behavior and knowledge of the Christian faith among both the clergy and laity, and he believed that for people to live good Christian lives they must have an understanding of the faith.In chapter seventy-two of the Admonitio Charlemagne asserted the responsibility of the bishops and monks of his kingdom to establish schools to teach the psalms, music and singing, and grammar, so that the boys of the kingdom could learn to read and write and so that those who wished to pray could do so properly. This program of religious and educational reform was restated in the circular letter on learning to the abbot Baugulf of Fulda, or De litteris colendis. In the letter Charlemagne emphasized the importance of learning and proper knowledge of the faith for living a good Christian life. The letter proclaims the need for the creation of more books and calls on the higher clergy of the realm to establish schools at churches and monasteries to educate young boys. The Carolingian Renaissance thus grew out of Charlemagne's desire to improve the religious life of the clergy and laity of his kingdom.To accomplish this end, Charlemagne needed scholars and books, and he managed to acquire both with little difficulty. Indeed, his wealth and power and program of religious reform attracted many of the greatest scholars of his age, many of whom received important positions in the Carolingian church. Among the more noteworthy scholars to join the Carolingian court were the grammarian Peter of Pisa and the Lombard Paul the Deacon, who wrote an important history of the Lombards. Theodulf of Orléans was another important figure, who joined the court from Spain and became a bishop and the author of significant theological treatises and legislation.Perhaps the greatest of the foreign scholars to join the court was Alcuin of York, whose importance was recognized in his own day. Alcuin brought the great Anglo-Saxon tradition of Bede and the Northumbrian revival of learning to the Carolingian realm. His was not an original mind, but his contribution to learning was exactly what Charlemagne needed; Alcuin's knowledge was encyclopedic, and his talents as a teacher were widely recognized. Indeed, his learning and pedagogy are revealed by the number of great students, such as Rabanus Maurus, the preceptor of Germany, who followed in Alcuin's tradition. Moreover, Alcuin brought books to the continent from England and remained in contact with his homeland throughout his life, which allowed him to import more books needed for the growth of learning under Charlemagne and his descendants. Alcuin also has long been associated with an important reform, the creation of the elegant and highly readable writing style known as Carolingian minuscule. Although his role is now recognized as less central in the creation of the script, he and his monastery at Tours did play some role in the development of Carolingian minuscule, which was to be admired and copied during the Italian Renaissance centuries later.The arrival of numerous scholars with their books stimulated learning throughout the realm, especially at the highest levels of society, where the renaissance had its greatest impact, as Alcuin and others began to teach and establish schools associated with cathedrals and monasteries. The new emphasis on learning contributed to the increased production of books, so central to the renaissance, and numerous books of Christian and pagan antiquity were copied in Carolingian monasteries. Indeed, one of the great achievements of the renaissance is the preservation of ancient Latin literature, and the earliest versions of many ancient Latin works survive from copies done by the Carolingians. Among the ancient Roman writers whose works were preserved by the Carolingians are Ammianus Marcellinus, Cicero, Pliny the Younger, Tacitus, Suetonius, Ovid, and Sallust. There were also important works of grammar and rhetoric copied in Carolingian scriptoria (writing rooms). But most important to the Carolingian rulers and scholars and central to their reform effort were the works of Christian authors, many of which were copied in the scriptoria.The most important book copied by the Carolingian scribes was the Bible, which was often divided into different volumes (e.g., collections of the Prophets, historical books, or Gospels), and a new edition of the Bible was one of Alcuin's many achievements. The scribes also copied the works of the great Christian writers of antiquity and the early Middle Ages, including Bede, Isidore of Seville, Cassiodorus, Pope Gregory the Great, St. Jerome, and others. Of course, St. Augustine of Hippo was also copied extensively, and the monastery at Lyons became a great center of Augustine studies.As important as the preservation of ancient manuscripts was, Carolingian scholars did much more than just have books copied. Indeed, the renaissance was marked by the production of many new books in a variety of disciplines. One noteworthy area of production was in the writing of history, biography, and hagiography. Carolingian authors wrote numerous saints' lives, as well as more traditional works of history and biography. One of the most famous contributions of the renaissance was the life of Charlemagne, written by his friend and advisor Einhard. The biography provides a somewhat idealized portrait of the great ruler, one that borrows heavily from the ancient Roman biographer Suetonius, but still provides important insights into the personality, appearance, and achievements of its subject. A later ninth-century writer, Notker the Stammerer, also wrote a life of Charlemagne for one his descendants that offers an even more idealized version of the great emperor's life. Charlemagne was not the only Carolingian to be immortalized in a biography, however. Louis the Pious was the subject of three biographies written in his own lifetime, including one in verse. Numerous annals were also written at the monasteries throughout the Carolingian realm, along with the semiofficial Royal Frankish Annals and the famous history of the civil wars of the mid-ninth century by Nithard.Carolingian Renaissance authors also wrote numerous commentaries on the books of the Bible, as well as treatises on proper Christian behavior. Alcuin, Theodulf of Orléans, and others wrote a number of treatises defending the Carolingian understanding of the faith against Adoptionists (Christian heretics who taught that Jesus was the son by adoption) in Spain, icon worshippers in the Byzantine Empire, and others who went astray. Manuals of education and Christian learning, an encyclopedic work by Rabanus Maurus, works of law and political practice by Hincmar of Rheims, and epistles of almost classical elegance by Lupus of Ferrieres were among other noteworthy works of Carolingian writers. Carolingian scholars also wrote Latin poetry. Their work may not be the most original or inspired, but it demonstrates the degree of sophistication they achieved, as well as providing great insights into the court of Charlemagne and its values.Although initiated by Charlemagne, the renaissance enjoyed its greatest achievements in the generations following his death. And there is perhaps no better witness of the intellectual confidence and maturity reached by the Carolingian scholars than the doctrinal controversies that took place in the mid-ninth century. One dispute, which concerned the exact nature of the Eucharist, involved the theologians Paschasius Radbertus and Ratramnus of Corbie. An even greater controversy involved the reluctant monk, Gottschalk of Orbais, and a great number of Carolingian theologians. The dispute revolved around Gottschalk's doctrine of predestination and his interpretation of the teachings of St. Augustine of Hippo. Gottschalk's teachings, which promoted the doctrine of double predestination (that is, both to hell and heaven), caused concern among the clergy, especially his bishop, Rabanus Maurus. The dispute attracted the attention of Hincmar of Rheims and the court royal of Charles the Bald. The king himself called upon the brilliant theologian, also the only Carolingian scholar with an understanding of Greek, John Scotus Erigena. His response to Gottschalk, however, was misunderstood by those around him and even further complicated the situation. That notwithstanding, the ability of the Carolingians to carry on high-level doctrinal debates demonstrates the maturity and sophistication of the Carolingian Renaissance.The achievements of the Carolingian Renaissance were not, however, limited to literary and theological works and book production. Carolingian artists and architects created a great number of brilliant works in the plastic arts. The most notable architectural monument of the Carolingian age, and one of the few remaining (because most buildings were made of wood), was the palace complex that Charlemagne, with the help of his chief architect, Einhard, built at Aix-la-Chapelle (modern Aachen, Germany). The palace was a magnificent structure, as the remaining portion, an octagonal chapel inspired by late Roman imperial models in Italy, suggests. Carolingian artists were skilled jewelers and goldsmiths and created beautiful works in ivory, often used as covers for manuscripts. But perhaps the most remarkable Carolingian works of art are the miniatures that illuminated numerous manuscripts of the late eighth and ninth centuries.Carolingian painting drew from a varied legacy of Roman, Christian, and Germanic influences. It clearly borrowed from ancient Roman models, its themes were often related to Christian themes and scenes from the Scriptures, and it incorporated the geometric designs and animal figures popular in Germanic traditions. Illustrations based on the Gospels and the Book of Revelation were popular, as were scenes depicting King David, an important figure in Carolingian political thought. Carolingian artists also left stunning depictions of the Evangelists, renderings of various Carolingian kings, and numerous representations of Christ in majesty, an image that had both religious and political connotations for the Carolingians. As with all aspects of the renaissance, Carolingian kings promoted painting, and the courts of Charlemagne and Charles the Bald were especially noteworthy for their support of art.

See alsoAdmonitio Generalis; Agobard of Lyons, St.; Alcuin of York; Ammianus Marcellinus; Anglo-Saxons; Augustine of Hippo, St.; Barbarian Art; Bede; Capitularies; Carolingian Dynasty; Cassiodorus; Charlemagne; Charles the Bald; Dhuoda; Einhard; Gottschalk of Orbais; Gregory the Great; Hincmar of Rheims; Isidore of Seville; Ivories; John Scottus Erigena; Letter to Baugulf; Louis the Pious; Nithard; Pippin III, Called Pippin the Short; Royal Frankish Annals; Theodulf of OrléansBibliography♦ Beckwith, John. Early Medieval Art. London: Thames and Hudson, 1969.♦ Brown, Giles. "Introduction: The Carolingian Renaissance." In Carolingian Culture: Emulation and Innovation, ed. Rosamond McKitterick. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994, pp. 1-51.♦ Cabaniss, Allen, trans. Son of Charlemagne: A Contemporary Life of Louis the Pious. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1961.♦ Contreni, John J. "The Carolingian Renaissance: Education and Literary Culture." In The New Cambridge Medieval History, vol. 2, ed. Rosamond McKitterick. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995, pp. 709-757.♦ Dutton, Paul. Carolingian Civilization: A Reader. Peterborough, Ont.: Broadview, 1993.♦ Einhard and Notker the Stammerer. Two Lives of Charlemagne. Trans Lewis Thorpe. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin, 1981.♦ Henderson, George. "Emulation and Invention in Carolingian Art." In The New Cambridge Medieval History, vol. 2, edited by Rosamond McKitterick. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995, pp. 248-273.♦ Hubert, Jean, Jean Porcher, and Wolfgang Fritz Volbach. The Carolingian Renaissance. New York: George Braziller, 1970.♦ Laistner, Max L. W. Thought and Letters in Western Europe, a.d. 500 to 900. 2d ed. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1976.♦ McKitterick, Rosamond. The Carolingians and the Written Word. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.♦ --- . The Frankish Kingdoms under the Carolingians, 751-987. London: Longman, 1983.♦ Mütherich, Florentine, and Joachim E. Gaehde. Carolingian Painting. New York: George Braziller, 1976.♦ Nelson, Janet. Charles the Bald. London: Longman, 1992.♦ Riché, Pierre. Education and Culture in the Barbarian West: From the Sixth to the Eighth Century. Trans. John Contreni. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1976.♦ --- . The Carolingians: A Family Who Forged Europe. Trans Michael Idomir Allen.♦ Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1993.♦ Scholz, Bernhard Walter, trans. Carolingian Chronicles: Royal Frankish Annals and Nithard's History. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1972.

See alsoAdmonitio Generalis; Agobard of Lyons, St.; Alcuin of York; Ammianus Marcellinus; Anglo-Saxons; Augustine of Hippo, St.; Barbarian Art; Bede; Capitularies; Carolingian Dynasty; Cassiodorus; Charlemagne; Charles the Bald; Dhuoda; Einhard; Gottschalk of Orbais; Gregory the Great; Hincmar of Rheims; Isidore of Seville; Ivories; John Scottus Erigena; Letter to Baugulf; Louis the Pious; Nithard; Pippin III, Called Pippin the Short; Royal Frankish Annals; Theodulf of OrléansBibliography♦ Beckwith, John. Early Medieval Art. London: Thames and Hudson, 1969.♦ Brown, Giles. "Introduction: The Carolingian Renaissance." In Carolingian Culture: Emulation and Innovation, ed. Rosamond McKitterick. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994, pp. 1-51.♦ Cabaniss, Allen, trans. Son of Charlemagne: A Contemporary Life of Louis the Pious. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1961.♦ Contreni, John J. "The Carolingian Renaissance: Education and Literary Culture." In The New Cambridge Medieval History, vol. 2, ed. Rosamond McKitterick. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995, pp. 709-757.♦ Dutton, Paul. Carolingian Civilization: A Reader. Peterborough, Ont.: Broadview, 1993.♦ Einhard and Notker the Stammerer. Two Lives of Charlemagne. Trans Lewis Thorpe. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin, 1981.♦ Henderson, George. "Emulation and Invention in Carolingian Art." In The New Cambridge Medieval History, vol. 2, edited by Rosamond McKitterick. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995, pp. 248-273.♦ Hubert, Jean, Jean Porcher, and Wolfgang Fritz Volbach. The Carolingian Renaissance. New York: George Braziller, 1970.♦ Laistner, Max L. W. Thought and Letters in Western Europe, a.d. 500 to 900. 2d ed. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1976.♦ McKitterick, Rosamond. The Carolingians and the Written Word. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.♦ --- . The Frankish Kingdoms under the Carolingians, 751-987. London: Longman, 1983.♦ Mütherich, Florentine, and Joachim E. Gaehde. Carolingian Painting. New York: George Braziller, 1976.♦ Nelson, Janet. Charles the Bald. London: Longman, 1992.♦ Riché, Pierre. Education and Culture in the Barbarian West: From the Sixth to the Eighth Century. Trans. John Contreni. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1976.♦ --- . The Carolingians: A Family Who Forged Europe. Trans Michael Idomir Allen.♦ Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1993.♦ Scholz, Bernhard Walter, trans. Carolingian Chronicles: Royal Frankish Annals and Nithard's History. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1972.

Encyclopedia of Barbarian Europe. 2014.